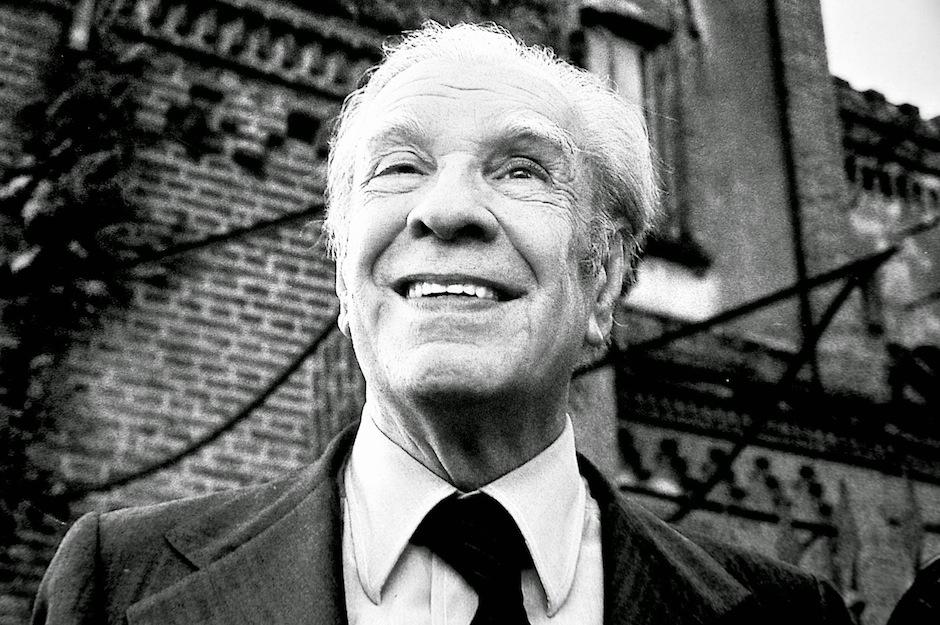

This legendary Argentine poet, essayist, and short-story writer's works have become classics of 20th-century world literature, leaving a legacy that serves as an enduring testament to the politics and passions of Jorge Luis Borges. Emma Zunz by Jorge Luis Borges by admin 2010/01 Returning home from the Tarbuch and Loewenthal textile mills on the 14th of January, 1922, Emma Zunz discovered in the rear of the entrance hall a letter, posted in Brazil, which informed her that her father had died. Jorge Luis Borges was born in Buenos Aires, in the house of his maternal grandparents, on Aug. His father, of Italian, Jewish and English heritage, professed the law but, as Mr. Argentine author Jorge Luis Borges exerted a strong influence on the direction of literary fiction through his genre-bending metafictions, essays, and poetry. Borges was a founder, and principal practitioner, of postmodernist literature, a movement in which literature distances itself from life situations in favor of reflection on the creative process and critical self-examination.

Jorge Luis Borges most famous works include Universal History of Infamy (1935), Ficciones (1944), The Aleph (1949), and The Book of Sand (1975). All of them deal with fictional places and toy with the idea of infinity and mythical creatures that immerse the reader in magical worlds. The stories have been influenced by all genres of literature, from ancient Greece through the 20th-century avant-garde movements.

One of the most famous Jorge Luis Borges excerpts is:

The universe (which others call the Library) is composed of an indefinite and perhaps the infinite number of hexagonal galleries, with vast air shafts between, surrounded by very low railings. From any of the hexagons, one can see, interminably, the upper and lower floors. The distribution of the galleries is invariable. Twenty shelves, five long shelves per side, cover all the sides except two; their height, which is the distance from the floor to ceiling, scarcely exceeds that of a normal bookcase.….

Jorge Luis Borges, The Library of Babel (1941)

Many consider the text a prophesy about the creation of Internet: a global library in which all texts are related and interlinked. According to Borges, the finite library represented the universe before mankind, although it would appear infinite to the human eye.

His stories, always full of detailed quotes, create logical syllogisms in the mind that make even the impossible seem possible. The words transform into bold images that make it seem like part of the real world.

Jorge Luis Borges was born in Buenos Aires on August 24th, 1899. He was the son of an Argentinian lawyer, Jorge Guillermo Borges, and his mother, Leonor Acevedo Suárez, was from Uruguay. At their sophisticated family home, both Spanish and English were spoken. Borges was exposed to literature very early on, and by age four he could already read and write.

At 9 years old, the writer was first published in the El País newspaper when he translated The Happy Prince by Oscar Wilde from English to Spanish. This is the only time that the author ever signed his name as simply “Jorge Borges.” During his childhood years, Jorge Luis Borges had a rough time and was constantly made fun of and humiliated by his classmates at his school in the Palermo neighborhood of Buenos Aires.

The Borges family moved to Europe when Jorge’s father was forced to retire from his position as a professor due to a blindness disease that would greatly influence his son. They settled in the city of Geneva, where Jorge Luis Borges would study French and teach himself German.

In 1919 the family moved to Barcelona and later to Palma de Mallorca, marking the beginning of Jorge Luis Borges’ professional literary career. In Madrid and Seville, he participated in the Ultraist movement and later became the leading force of the movement in Argentina. There, Borges associated with other important Spanish writers of the time: Rafael Cansinos Assens, Gómez de la Serna, Valle Inclán, and Gerardo Diego.

In 1921 Jorge Luis Borges returned to his native Buenos Aires. The rediscovery of his homeland greatly impacted him and led him to mystify its suburbs, the tango, and even the neighborhood hoodlums. He befriended both Leopoldo Lugones and Ricardo Güiraldes, with whom he founded a new literary magazine.

When Juan Perón took power in Argentina, Borges, an anti-Peronist, abandoned his regular position and dedicated himself to giving lectures throughout the Argentinian provinces.

By the age of 50, Jorge Luis Borges had finally gained the recognition that he deserved both inside and outside of Argentina. He eventually became the president of the Argentine Society of Writers and, with the fall of Perón in 1955, was named the president of the National Library.

In 1986 Jorge Luis Borges returned to Geneva, a city he dearly loved, where he passed away from liver cancer on June 14th of the same year.

The Queer Use of Communal Women in Borges'

'El muerto' and 'La intrusa'

'El muerto' and 'La intrusa'

Herbert J. Brant

Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis

Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis

Sex and women are two very problematic components in the fiction of JorgeLuis Borges: the absence of these two elements, which seems so casual andunremarkable, really highlights the strangeness of their exclusion. Forexample, scenes of sexual acts are almost totally lacking in Borgesian writing(Emma Zunz's sexual encounter with an anonymous sailor is the most notableexception) and even the most veiled suggestion of erotic activities is limitedto only a very few stories. Similarly scarce,[1] too, are female characters who figureprominently in the narration and who seem to possess a independentpersonhood.[2] The fictional world created byBorges is a place where women, if they appear at all, seem to exist mainly asdebased objects[3] for the purpose of providingmen with an opportunity for sex and where such sexual activities, by means of afemale body. Sex and women are used primarily as bargaining chips in therelationship between men, never for the traditional purposes of eitherprocreation or pleasure. Sex in Borges' fiction, by means of an objectifiedfemale body,[4] is nothing more than a maneuverthat gives definition and dynamism to the interaction between men.

In opposition to the traditional critical standpoint that male-maleinteraction in Borgesian fiction is merely homosocial and, therefore, purelynonsexual, a closer inspection of Borges' work reveals the clear but playfullyveiled presence of homoerotic desire. My purpose here is to analyze twostories, 'El muerto' and 'La intrusa,' to expose the way in which thehomosocial element of Borges' fictional world slides across the continuum[5] towards the homosexual side when men in eachstory make use of a communal woman for the purpose of connecting physically andemotionally with another man. In these two stories, the erotic desire of thetwo men is plainly not directed towards a female, but rather towards eachother, with the female as the intermediary focal point at/in which the two menmay coincide. This type of sexual activity has the dual objective offulfilling the societal mandate of 'compulsory heterosexuality' when the malesuse the requisite female body for sexual purposes, while at the same timecircumventing the proscription of male homosexual contact.[6] In other words, Borges has substituted anintervening female body between the men as a way to permit the men to connectphysically without transgressing heteropatriarchal prohibitions. In thismanner, Borges is able to give expression to a relationship between men thatsimultaneously attracted him and repulsed him.

In this study I explore the similarities, differences, and significance inthe use of the shared woman in 'El muerto' and 'La intrusa' and I propose that,far from the traditional critical appraisal, voiced by Robert Lima, that'Borges has concerned himself with heterosexual relations to the exclusion ofother types' (417),[7] sexual acts in Borges'fiction are not only homosocial, but also, in most cases, homosexual. Despitesome rather substantial similarities between the two stories, 'El muerto' and'La intrusa' provide two very different portrayals of the union of two menthrough the body of a woman. The setting for both stories, for example, islocated outside urban society, that is, on the plains of the Río de laPlata basin. The time period for both stories is the 1890s. The malecharacters in both stories are known to be violent, severe, and willing to killfor their honor in stereotypical macho fashion. But aside from theseparallels, the two stories have markedly different outcomes and purposes. In'El muerto,' one man desires to coincide with another and through the use of acommunal woman, the two men are connected in a way that creates a shift inauthority, leading the second man to seek revenge on the first for histransgression of the male power dynamic. In 'La intrusa,' two brothers,through the use of a communal woman, suddenly come to understand how much theydesire each other and once their passion is recognized, they preserve andreinforce it by disposing of the barrier between them, the woman who broughtthem together.

'El muerto,' originally published in 1946 and later collected in the firstedition of El Aleph (1949), is the story of a handsome youngcompadrito from Buenos Aires, Benjamín Otálora, who haskilled a man and must leave the country. He heads for Uruguay with a letter ofintroduction for Azevedo Bandeira, a local caudillo. While searchingfor this Bandeira, he participates in a knife-fight and blocks a lethal blowintended for the man he discovers later to be Bandeira himself. Having earnedBandeira's trust and gratitude, Otálora joins his band of gauchosmugglers. Little by little, Otálora becomes more greedy and ambitious,taking more risks, making more decisions, and befriending Bandeira's bodyguard, Ulpiano Suárez, to whom he reveals his secret plan to takeBandeira's place as leader of the group. The plan is the result of his desireto possess Bandeira's most important symbols of power: his horse, his saddle,and his woman with the bright red hair. One day, after a skirmish with a rivalband of Brazilians, Otálora is wounded and on that day, he ridesBandeira's horse back to the ranch, spills blood on the saddle, and sleeps withthe woman. The end of the story occurs on New Year's Eve in 1894 when, after aday of feasting and drinking, at the stroke of Midnight, Bandeira summons hismistress and brutally forces her to kiss Otálora in front of all themen. As Suárez aims his pistol, Otálora realizes before he diesthat he had been set up from the very beginning and that he had been permittedthe pleasure of power and triumph because in the end, to Bandeira, he never wasanything more than a soon-to-be dead man.

The usual critical stance regarding this story emphasizes the time-honoredview that in this tale, as in similar stories such as 'La muerte y labrújula,' Borges is showing the reader the inherent foolishness of thehuman presumption that we are in control of our own destinies. Jaime Alazraki,for example, states that 'El muerto' demonstrates a 'tragic contrast between aman who believes himself to be the master and the maker of his fate and a textor divine plan in which his fortune has already been written' and that thiscontrast 'parallels the problem of man with respect to the universe: The worldis impenetrable, but the human mind never ceases to propose schemes' (19).George R. McMurray makes the case that the story symbolizes 'the absurdcondition of all men who strive for success without suspecting that fate--oftena fate of their own making--is all the while plotting their destruction' (21).Gene H. Bell-Villada notes that the tale 'is a thriller with parable overtones;it has the ring of those old moral fables in which the harshly sealed fate ofone overly presumptuous individual seems to stand as a cautionary tale to usall' (182). E. D. Carter, too, indicates that the ending of the story is aclear illustration of the 'punishment' that awaits the man who tries to createhis own destiny by challenging a force greater than himself (14). Despite thestriking consensus among most critics that Otálora is struck downbecause of his ambition and greed, the element that seems to go almostunperceived and uncommented is his desire to possess not only Bandeira's powerand prestige, but also his person; Otálora wants to be Bandeira, to bein him and to see as he sees, to feel as he feels, to possess what hepossesses. The desire for one man to be inside another man, to coincide withhim, to possess him, is undeniably homoerotic.

The two central characters of the story are, as McMurray has noted,'antithetical doubles' (20): Otálora is a strapping young lad('mocetón') of Basque descent with light coloring, while the olderBandeira 'da, aunque fornido, la injustificable impresión de sercontrahecho' and whose mixed ancestry of Portuguese Jew, African, and NativeAmerican underscores his darkly colored patchwork appearance (Aleph42).[8] Common between the two, however, alink that unites them, is the remarkably significant Borgesian facial scar. AsI have shown elsewhere,[9] the visible scar inBorges has the value of marking a man for all the world to see as one who isbrave and manly on the outside, but whose macho exterior is merely a maskdisguising a deceitful and, therefore, feminine interior. In other words, aman whose homosocial character has transgressed the line of homosexual desire(a 'man's man' who has become 'interested in men'), is permanently branded byan object (a knife or sword) that symbolizes what he most desires (thephallus). Western cultural norms dictate that those men who violateheteropatriarchal traditions by loving other men must be of inferior moralstatus and this condition is given tangible form: as Cirlot explains,'[i]mperfecciones morales, sufrimientos ([[questiondown]]son lo mismo?) son,pues, simbolizados por heridas y por cicatrices de hierro y fuego' (127;emphasis added).

Otálora's desire for Bandeira is signaled from the very beginning oftheir association by the young man's intense need for visual contact; heyearns to see the man he desires and to be seen and recognized by him. Forexample, shortly after becoming a part of Bandeira's group, during his gauchoapprenticeship, the narrator mentions that Otálora is only able to seeBandeira once, but that 'lo tiene muy presente.' To add to the older man'sdesireability, Otálora is reminded by the others that Bandeira is themaster and model ('ante cualquier hombrada, los gauchos dicen que Bandeira lohace mejor') and Bandeira becomes, for Otálora, an absent but urgentlycoveted object of desire. Otálora, in an attempt to get Bandeira totake special notice of him, to make Bandeira see him, wounds one of his gauchocompañeros in a fight and takes his place on a smuggling missionso that his cunning and daring will be noted by Bandeira. Otálora hopesthat Bandeira will suddenly realize that 'yo valgo más que todos susorientales juntos' (Aleph 45; original emphasis). Once he returnsto the Big House, the narrator again notes that 'pasan los días yOtálora no ha visto a Bandeira' (Aleph 45). Otálora'sdesire for contact with Bandeira through a male-male gaze is an earlyindication of his longing to connect with the man he wishes to replace.

As Otálora's hunger for Bandeira grows, he begins to crave Bandeira'smany different possessions so that he can satisfy his desire through ametonymic ownership of things contiguous to Bandeira. When Otálorafirst sees Bandeira's bedroom, the first objects that he notices are highlysymbolic: 'hay una larga mesa con un resplandeciente desorden de taleros, dearreadores, de cintos, de armas de fuego y de armas blancas' (Aleph 46).These objects are traditionally linked to both masculine sexuality and thedominance/domination and violent power of masculine gender. Otálora'sinterest in and appetite for these specifically masculine attributes ofBandeira is highlighted when the narrator describes the objects on the tablewith the adjective 'resplandeciente' while in contrast, when another ofBandeira's 'objects,' his mistress, enters the room barefoot and bare-breasted,Otálora observes her indirectly (as a reflection in a mirror) with only'fría curiosidad' (Aleph 46).

Otálora's desire for Bandeira's prized possessions is a clear exampleof René Girard's conceptualization of 'triangular desire.' SharonMagnarelli, in her study of women in Borges' fiction, summarizes Girard'sthesis, stating that 'desire is dependent upon a triangular relationship: theobject of desire (O) is desirable to one individual (A) to the extent that itis desired by another (B).' She notes, further, that 'the object of desire (O)is an empty receptacle needing to be filled with what is projected upon it bythe subjects of that desire (A and/or B)' (143). Applying this model oftriangular desire to the fiction of Borges, Magnarelli finds that his femalecharacters often serve the function of desired objects in a triangle and it isthrough these objects that sexual intercourse becomes 'the gesture which linksall men...' (143).

Magnarelli indicates that the result of this triangular relationship, soabundant in Borges' fiction, is what has usually been called simply 'rivalry.'But this rivalry in Borges is never the consequence of a powerful tie between aman and a woman, but rather between two men. Sedgwick, in applying Girard'stheory to English literature, extends Girard's theory and finds that therivalry between two men that is expressed through desire for the same woman isa bond 'as intense and potent as the bond that links either of the rivals tothe beloved.' In fact, 'the bond between rivals in an erotic triangle [is]even stronger, more heavily determinant of actions and choices, than anythingin the bond between either of the lovers and the beloved' (21). In Borges, aswe will see, the action that is determined in response to the rivalry oftriangular desire is always violent.[10]

In 'El muerto,' Otálora fervently desires to take possession ofseveral different prized objects belonging to Bandeira: his horse with itssaddle and blanket, and the red-headed woman. Otálora wants them withso much intensity precisely because Bandeira has invested so much desire inthem, or as Magnarelli puts it, 'the objects are coveted because the prestigeof Bandeira has been projected on them; they have no intrinsic value' (144).Indeed, Otálora does not desire the horse for its equine qualities, nordoes he desire the mistress for her feminine qualities.[11] And although they may not possess anintrinsic value, they do have a functional one. Unlike other objects thatsymbolize Bandeira's power,[12] the saddle onthe horse and the woman are two things on/in which the two men can physicallyconnect: when Otálora mounts first the horse, and then later mounts thewoman, he is, in effect, mounting Bandeira himself.

Once he achieves his objective and comes into possession of all of Bandeira'smost valued objects, Otálora enjoys his triumph at a New Year's Evecelebration. Otálora has fulfilled his desire to coincide withBandeira, to connect with him indirectly through the body of the red-headedwoman and although he does not know it yet, he must now die. Otálora'sdeath is required, not simply because he was too ambitious and too greedy andtried to take command of things that he had no right to control, but because hehas dared to place himself in the position of power in the 'unimaginablecontact'[13] that would turn Bandeira into theso-called 'passive' partner in male-male sexual intercourse. As Borges himselfmade clear in his 1931 essay 'Nuestras imposibilidades,' among the Buenos Airesgangsters and hoodlums there is no shame for the 'active' partner in'sodomy,'[14] 'porque lo embromó alcompañero' (Discusión 16-17) while it is only the'passive' partner who suffers dishonor and condemnation. The affront thatBandeira must avenge is his 'getting screwed' by Otálora, the fact thathe finds himself in the shameful and feminized position of receptor inthe contact between them.[15]

Bandeira's revenge takes place precisely when Otálora's pleasure andexcitement are at its peak. In fact, the narrator's description gives theclear impression that Otálora has a metaphorical erection, symbolizinghis active, inserter role: 'Otálora, borracho, erigeexultación sobre exultación, júbilo sobre júbilo;esa torre de vértigo es un símbolo de su irresistibledestino' (Aleph 49; emphasis added). As long as Otálora isalive, wielding his power as macho inserter, Bandeira cannot recover his roleas the regional strongman. The narrator is careful to note that when Bandeiraspeaks at the end of the story, he speaks 'con una voz que se afemina yse arrastra' (Aleph 50; emphasis added). Weakened by the feminizedposition in which Otálora has put him, Bandeira himself cannot wreak hisvengeance on Otálora; that job is left to Suárez whosymbolically and violently penetrates Otálora with a gunshot andconsequently destroys the rival that had appropriated Bandeira's phallicpower.[16]

The story, 'La intrusa,' offers quite a different outcome from that of 'Elmuerto.' In this story, rather than the death of a man who dares to usurpmale sexual power from another man by means of a communal woman, in 'Lainstrusa' it is the communal woman who must die in order to cement the bonds ofdesire between two men. 'La intrusa' was first printed in the third edition ofEl Aleph (1966) and was later included in the collection, El informede Brodie (1970). It is the story told of two brothers, Cristiánand Eduardo Nilsen, who were infamous for both their rough and brutal ways aswell as their unusual closeness. According to the legend, the incidents occurin the 1890s when the elder brother, Cristián, brings home a prostitutenamed Juliana Burgos. When Eduardo 'falls in love' with her, too, rather thanstarting a terrible fight, Cristián tells him to 'use' her if he likes.Soon, their joint use of Juliana gives rise to an emotional tension between thetwo brothers and in order to resolve the conflict, Cristián decides tosell Juliana to a brothel outside of town and share the money with his brother.Unfortunately, their need to share her continues as they both make trips to seeher at the bordello. Cristián decides to buy Juliana back and take herhome again. But the jealousy between the two brothers becomes worse. Finally,on a Sunday, Cristián tells Eduardo that they must take a trip to sellsome 'skins.' When they arrive at a deserted field, Cristián confessesthat he has killed Juliana and put an end to their disharmony. The brothersembrace, almost crying, linked even more closely by this 'sacrifice.'

This story, unlike the majority of Borges' tales, has occasioned quite widelydivergent views among critics with respect to its content and artistry. Somecritics have found the story's content to be quite troubling, even alarming,and that the narration seems to signal a clear break with Borges' earlier, thatis, more accomplished style. For example, Bell-Villada, with particularlyforceful condemnation, finds that '[i]t seems almost inconceivable that thesame man who created `Emma Zunz' could also have written `The Intruder,' adisturbing yarn of jealousy and frontier violence that implicitly celebrates amale companionship strengthened by misogyny' (188). Bell-Villada continues toberate the work, concluding that despite its 'polished prose,' the story isshallow and sketchy and that '[i]t goes without saying that the story'sgratuitous violence against a female can only strike negative chords at thismoment in history' (189). Martin Stabb also remarks that '[a] superficialreading of this piece might suggest that it was the work of another writer,certainly not the Borges of Ficciones and The Aleph. [...]...the story itself--revolving around crudeness, sex, and prostitution--washardly reminiscent of the Borges of earlier years' (86). Stabb, however, doesgo on to link this story with Borges' 'canonical' texts, especially throughthematic content. Gary Keller and Karen Van Hooft, too, argue that there is acontinuity between Borges' earlier and later production but that this storyincorporates significant innovations in Borgesian narrative, particularly thedevelopment of plot as depending less on 'the familiar devices of magic, theexotic, or game-playing' and more 'on a psychologically authentic succession ofgrave actions and enhanced self- and other-awareness' (300).

But most critics do seem to agree on one thing: the theme offriendship/fraternity as an ultimate goal over heterosexual love/sex. McMurray(143) views this theme as a result of Borges' fascination for the cult of'machismo' and this idea is echoed by Bell-Villada who states that '[t]he tiestressed here, of course, is of a rather archaic sort, the macho bonds betweenmen in the wilderness, a relationship of the kind one might encounter at allmale clubs, on athletic teams, or in men's-magazine stories about deer hunting'(189). Lima (and repeated in Carter), however, makes the case that Borges'personal fear and loathing of sex and sexuality are the basis of the theme.[17] Lima concludes that in killing the woman,Cristián 'has confronted the erotic `demon' in himself and executed it.He has opted for the fraternal rather than for the sexual bond' and this is dueto 'Borges' view that coition, because of its appeal to man's lower nature, canfunction only as a means to an end. In this instance, that end is thereaffirmation and strengthening of fraternal ties' (415).

The question in this story of fraternal love that has crossed over on thehomosocial-homosexual continuum to the homosexual side has been an issue sincethe story first appeared. For some critics, the homosexual implications of theNilsen brothers' relationship can be neutralized by Borges' use of a femaleintermediary, while for others, she is the catalyst to a more physical bondingbetween the brothers. Lima's conclusion above, however, indicates that thereare those that cannot conceive of the possibility that fraternal bonds andsexual bonds can coincide, that brothers can also be lovers. And it isimportant to note that among those who cannot imagine brothers as sexualpartners is the author himself.[18] In fact,according to Emir Rodríguez Monegal and Alastair Reid, the tale is basedon a real incident that Borges found necessary to modify: the 'chiefalteration was to make the protagonists brothers instead of close friends, toavoid any homosexual connotations. (Perhaps unwillingly, he added incest)'(361). Canto, too, states that when she discussed the story with Borges, '[l]edije que el cuento me parecía básicamente homosexual.Creí que esto--él se alarmaba bastante de cualquieralusión en este sentido--iba a impresionarle. [...] Para él nohabía ninguna situación homosexual en el cuento. Continuóhablándome de la relación entre los dos hermanos, de la bravurade este tipo de hombres, etc.' (230).[19]

In spite of Borges' objections and his attempts simultaneously to expose anddisguise the nature of the relationship between the brothers, I have no doubtthat there is a clear homosexual content in the story. For example, theopening epigraph, indicated only by the chapter and verse designation '2 Reyes,I, 26,' seems to announce the theme of fraternal love. But, as Balderstonpoints out, this is one of Borges' clever deceptions to express and, at thesame time, suppress the homosexual context he would establish for the story.The biblical reference that Borges gives is, as Woscoboinik has mentioned, a'picardía' that bashfully disguises its own content (129). Balderstonexplains that '[t]he first chapter of the second book of Kings does nothave a twenty-sixth verse, but the second book of Samuel, sometimes alsoknown as the second book of Kings, contains the most famous of alldeclarations of homosexual love: `I am distressed for thee, my brother,Jonathan: very pleasant hast thou been unto me; thy love to me was wonderful,passing the love of women' (35). Once the reader has deciphered the referenceand found the actual passage, it becomes clear that the epigraph sets up thestory as one that will convey the power of a man's passion for another man, alove that will surpass the love of a woman.

Several details indicate that the Nilsen brothers are not like the other menof the region. First of all, their peculiar nature makes them unusuallyremoved and antisocial: no one dares intrude on their privacy and they neverlet people into their house because the brothers 'defendían su soledad'(Brodie 18). Furthermore, they are of an uncertain ethnic lineagewhich makes them appear physically different: '[s]é que eran altos, demelena rojiza. Dinamarca o Irlanda, de las que nunca oirían hablar,andaban por la sangre de esos dos criollos' (Brodie 18);'[f]ísicamente diferían del compadraje que dio su apodo forajidoa la Costa Brava' (Brodie 19). The narrator concludes that it is thisphysical difference, as well as 'lo que ignoramos, ayuda a comprender lounidos que fueron. Malquistarse con uno era contar con dos enemigos'(Brodie 19; emphasis added). What makes them distant, what makes themso odd, but above all, what makes them so close, is due to something wedo not and cannot know. Given the context of the rest of the story, however,the narrator's feigned ignorance appears to be a clear case of not being ableto name explicitly the 'peccatum illud horribile, inter christianos nonnominandum,' that is, homosexuality, the love/sin that dare not speak its name.

It is significant that immediately following the acknowledgment that thenarrator is unaware of what causes the two men to be so attached to each other,he mentions their sexual customs: it is known that their 'episodios amorosos'have only ever been sexual encounters with prostitutes. It is clear that thebrothers have never courted a woman with whom they could consider maintaining along-term relationship or with whom they could satisfy the heteropatriarchaldictate of marriage. So when Cristián brings the prostitute JulianaBurgos home to live with them, his intention is not to form a heterosexualbond, but rather to acquire a live-in maid ('[e]s verdad que ganaba asíuna sirvienta'), and more importantly, to be able to show her off as hiscompanion when he goes out in public ('la lucía en las fiestas')(Brodie 19). This second use of Juliana as a visible heterosexualpartner--a 'beard'--is quite necessary to deflect the already circulatingaccusations of homoerotic desire between the brothers as the narrator suggestswith a modest coded phrase, 'la rivalidad latente de los hermanos'(Brodie 20; my emphasis).

The most valuable use of Juliana, however, is her position as a sexualintermediary between the brothers. She is the third point of the love triangleand as such, '[s]he... has no intrinsic value, her value is the result of themediator's, the other's prestige. Cristián desires her because Eduardodoes and viceversa' (Magnarelli 144). So as the brothers share her, connectingman-to-man through her body, Juliana loses any identity as a human being andbecomes a mere sexual apparatus that permits the two men to have intimatephysical relations with each other without actually engaging in male-malesexual intercourse. The understanding of the true nature of their relationshipemerges when, as Keller and Van Hooft demonstrate, 'Juliana comes to serve as acatalyst and a foil for a more profound intrusion--the emergence of a consciousawareness of fraternal love, an awareness which is intolerable to the brothers'(305). This frightening knowledge, as Balderston points out, is 'what Sedgwickand others have called `homosexual panic' (35), the startling realization thata man's relationship to another man could be construed as homoerotic and must,therefore, reveal (unconscious) homosexual desire.

Their mutual desire ('aquel monstruoso amor' Brodie 22; myemphasis), however, becomes so overwhelming that the brothers must find arelease from the tension it causes. After a long discussion, the two mendecide to sell Juliana to a brothel and in that way they may succeed ineliminating the instrument that makes their physical love possible and incalming their own homophobic feelings of guilt. This response does not solvethe problem. Their need to connect through her grows more powerful than theirfear of acknowledging their homosexual passion for each other. As a result,the brothers are forced to buy her back after they visit her repeatedly in anattempt to recreate the erotic structure that once united them. From aninitial state of homophobic panic, the two brothers come to accept their desirefor each other and their need to bond in a more complete manner. The trueunion of the two brothers, however, will require the elimination of Juliana.

Despite the seeming inevitability of the conclusion of the story, the tragicmurder of Juliana Burgos[20] poses seriousdifficulties in the interpretation of the meaning of the relationship betweenthe brothers and to the communal woman that brings them together. For me, thedeath of Juliana at the hands of the Nilsen brothers is not a Christ-likesacrifice 'to atone for their `sin' of love,' as McMurray would have it (144),nor is it a sacrifice of their despised homosexuality and the destruction oftheir inner femininity, as Magnarelli concludes (148). These and otherinterpretations[21] fail to take into accountthe strength of the passion between the two brothers, which, as the epigraphreminds us, 'passes the love of women.' Cristián kills Juliana, notbecause he hates this woman or women in general, but rather because as long asJuliana exists as an intermediary, an impediment that keeps the brothers fromrealizing fully their homoerotic desire, the two men will never be able toconnect to each other directly. The two need to move beyond a relationshipwith a communal woman as surrogate to a relationship with their true object ofdesire. In order to accomplish this, they remove the obstacle that keeps themapart and through this 'sacrifice,' they are joined permanently in a moreintimate way.

Borges' fictional world is an essentially and unquestionably homosocialspace. In the vast majority of his stories, where there is a total absence offemale characters or where they are merely decorative, the homosociality in thetexts only hints at a possible queer sexuality between the male characters.But as the two stories 'El muerto' and 'La intrusa' show, the presence of afemale deployed as a structural element of the plot has the paradoxical effectof highlighting and underscoring the sexual nature of the relationships amongmales. Were it not for the inclusion of the red-headed woman in 'El muerto,'Otálora's scheme to unite with Bandeira and rob him of his male sexualpower could never have taken place. Unlike the other cherished objects such asthe horse and saddle which merely suggest an undercurrent of sexuality,Bandeira's woman provides a site at which the sexual aspect of Otálora'sdesire can be given more complete expression. Likewise, the presence ofJuliana Burgos in 'La intrusa' furnishes the Nilsen brothers with a physicallink through which they can fulfill their heretofore unacknowledged and growingpassion for each other. Their fame in the community for being both strange andunusually intimate implies from the very beginning that all they need is acatalyst to change their homosocial relationship into a homosexual one. It isJuliana, in her role as communal sexual body, that provides the transformativeelement. In the end, the use of communal women in these stories serves toprovide only the appearance of fulfilling the mandates of 'compulsoryheterosexuality,' while underneath this façade of sex between men andwomen it becomes quite plain that something very queer is going on.

WORKS CITED

Agheana, Ion T. Reasoned Thematic Dictionary of the Prose of Jorge LuisBorges. Hanover [NH]: Ediciones del Norte, 1990.

Altamiranda, Daniel. 'Borges, Jorge Luis (Argentina; 1899-1986).' LatinAmerican Writers on Gay and Lesbian Themes: A Bio-Critical Sourcebook.Ed. David William Foster. Westport: Greenwood P, 1994. 72-83.

Balderston, Daniel. 'The Fecal Dialectic: Homosexual Panic and the Origin ofWriting in Borges.' [[questiondown]]Entiendes? Queer Readings, HispanicWritings. Eds. Emilie L. Bergmann and Paul Julian Smith. Durham: DukeUP, 1995. 29-45.

Bell-Villada, Gene H. Borges and His Fiction. A Guide to His Mind andArt. Chapel Hill: U of North Carolina P, 1981.

Borges, Jorge Luis. El Aleph. Buenos Aires: Emecé, 1989.

---. Discusión. 1st ed. Buenos Aires: M. Gleizer, 1932.

---. El informe de Brodie. Madrid: Alianza, 1970.

Brandes, Stanley. 'Like Wounded Stags: Male Sexual Ideology in an AndalusianTown.' Sexual Meanings: The Cultural Construction of Gender andSexuality. Eds. Sherry B. Ortner and Harriet Whitehead. Cambridge:Cambridge UP, 1981. 216-239.

Brant, Herbert J. 'The Mark of the Phallus: Homoerotic Desire in Borges' `Laforma de la espada'.' Chasqui (in press).

Canto, Estela. Borges a contraluz. Madrid: Espasa-Calpe, 1989.

Carter, E.D., Jr. 'Women in the Short Stories of Jorge Luis Borges.'Pacific Coast Philology 14 (1979): 13-19.

Jorge Luis Borges Libros

Cirlot, Juan-Eduardo. Diccionario de símbolos. 3rd edition.Barcelona: Editorial Labor, 1979.

Dorfman, Ariel. 'Borges and American Violence.' Some Write to the Future:Essays on Contemporary Latin American Fiction. Trans. George Shivers withthe Author. Durham: Duke UP, 1991. 25-40.

Hughes, Psiche. 'Love in the Abstract: The Role of Women in Borges' LiteraryWorld.' Chasqui 8.3 (May 1979): 34-43.

Keller, Gary D. and Karen S. Van Hooft. 'Jorge Luis Borges' `La intrusa:' TheAwakening of Love and Consciousness/The Sacrifice of Love and Consciousness.'The Analysis of Hispanic Texts: Current Trends in Methodology. Eds.Lisa E. Davis and Isabel C. Tarán. New York: Bilingual P, 1976.300-319.

Lima, Robert. 'Coitus Interruptus: Sexual Transubstantiation in the Works ofJorge Luis Borges.' Modern Fiction Studies 19 (1973): 407-417.

Magnarelli, Sharon. 'Literature and Desire: Women in the Fiction of JorgeLuis Borges.' Revista/Review Interamericana 13.1-4 (1983): 138-149.

McMurray, George R. Jorge Luis Borges. New York: Frederick Ungar,1980.

Molloy, Sylvia. Signs of Borges. Trans. Oscar Montero. Durham: DukeUP, 1994.

Rivero, María Cristina. 'Interpretación y análisis de `Elmuerto'.' Universidad [Santa Fe] 77 (1969): 165-193.

Rodríguez Monegal, Emir. Jorge Luis Borges: A LiteraryBiography. New York: Paragon House, 1988.

--- and Alastair Reid, eds. Borges: A Reader. A Selection from theWritings of Jorge Luis Borges. New York: E.P. Dutton, 1981.

Sedgwick, Eve Kosofsky. Between Men: English Literature and MaleHomosocial Desire. New York: Columbia UP, 1985.

Silvestri, Laura. 'Borges y la pragmática de lo fantástico.'Jorge Luis Borges: Variaciones interpretativas sobre sus procedimientosliterarios y bases epistemológicas. Eds. Karl Alfred Blüherand Alfonso de Toro. Frankfurt am Main: Vervuert Verlag, 1992. 49-66.

Stabb, Martin S. Borges Revisited. Boston: Twayne, 1991.

Jorge Luis Borges

Woscoboinik, Julio. El secreto de Borges. Indagaciónpsicoanalítica de su obra. Buenos Aires: Editorial Trieb, 1988.

Back to LASA95 Pilot Project page.